California Yesterday

Reading Time: 12 Minutes

Saying good-bye to Los Altos Hills was hard. We’d been far out in the country and – save some minor inconveniences – we loved it. Mom bemoaned at one point that she and Babe were the only females “within a mile radius.” Still, we relished being so independent and our family was forged in this beautiful (almost civilian) setting. I was the eldest of four boys – each born at a different stop along the way. Just as Stan was born soon after we arrived in ‘the hills,’ Taylor would arrive on our way out the door and down the coast.

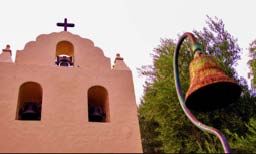

Dad got out a map and showed me where he had rented yet another temporary house in a town named Coronado, just across the bay from San Diego. I was a little pleased with myself that I knew our route and could trace it on the rest of the map. Social studies at school featured a book entitled California Yesterday and I found myself almost reciting history… An original coastal road was blazed as the earliest church missions were built, one at a time, south to north from Baja to San Francisco. The roadway was cut and formed as the procession traveled – in anticipation of royalty visiting the missions, as tradition dictated. Hence, El Camino (the highway) met Real (royal). This church settlement was the first traverse of the ‘Royal Road’ or ‘King’s Highway.’

We headed south on the paved modern version – California Route 101. I figured San Luis Obispo (one of the Mission sites) would mark halfway. We spent the night close by in Pismo Beach, meeting up with Mom, Sidney, and Taylor in the station wagon. By next evening we were driving around the perimeter of our new hometown, marveling at the natural beauty and feeling the gentle ocean breeze.

There were no traffic lights on ‘the island’ when we arrived and the only way to get across to San Diego efficiently was by ferry. As businesses and base jobs got to quitting time, half of Orange Avenue would line up with cars patiently waiting to drive down the clanging set of platforms to a parking space on one of four functioning ferry boats. When loaded, a ferry’s imminent departure was blasted by its horn’s obligatory basso profundo. The screws engaged, dark water stirred to a white froth, and the wide white boat itself lumbered out into the bay. Over and over ferries replaced one another until the cars were gone and the cries of seagulls slowly displaced nautical industrial noise.

Such rhythms and rituals in any community have their counterpoint – and juxtaposing the bay’s utilitarian frame was the ocean. Less than a mile away, waves crested and crashed on a wide stretch of white sand – the bay’s bookend boundary before an infinite Pacific horizon. The bay side was still and seemed humdrum compared to the salt in your sinuses and majestic drumbeat of ocean waves. Few views in life epitomize freedom like the sweep of Coronado beach.

Emanating from North Island, a slow but ubiquitous ‘whoppa whoppa whoppa’ pulsed day and night. Pilots-in-training constantly hovered helicopters at low altitude as part of their protocol. As unusual as it sounds, this almost musical rhythmic accompaniment was comforting. It was a subsonic reminder of where you lived. Oddly, when it stopped for one reason or another that got your attention. Putting any particulars aside, Coronado was a natural fit for a Navy town. But it was also, as all California seaside communities would come to know over the years, virgin territory… just another sleepy, seaside southern California town – innocently crested on the brink of being discovered, invaded, and finally overrun by developers and real estate agents. (Coronado isn’t Coronado any more.)

Officers, enlisted personnel, and their families occupied half of the homes (as still affordable) in this enclave and the grid of streets was usually teeming with kids. Literally – a grid. With no other reason to suspect engineers hastily designed a town, the fact that the large middle consisted of Avenues A, B, C, D… and (you guessed it) Streets designated first, second, third, through tenth might convince. An aberrant periphery of curvy streets framed the centered choc-a-bloc. Any map featured this checkerboard framed by the filigree of older, original roadways and homes. Any other location was related as coordinates. Our family house was on A Avenue near 6th Street – 547 “A” – and with just that much information, any kid in Coronado could find you.

There was one other important dynamic to a high concentration of Navy families in a small area – something no one talked about. This was the one important topic without a chapter in Mom’s unofficial guidebook – her dog-eared copy of The Navy Wife.

There was no chapter about fear.

When you have as many husbands and wives this close together, many doing dangerous work, fear leaks into the routine. Gradually, the luster of living in a seaside village combined with the patriotic verve endemic in military communities dims.

As stark reality about the job sinks in, the crisscross of Coronado’s backyard fences was a natural, private place for hard conversations between or among military spouses. Some of the fences heard the breezy conversation of denial. But just as many neighborly exchanges became tearful confessionals. This life wasn’t for everybody. To be sure, even in the earliest days, many family members found it difficult to stoically march through routines at the commissary or the gas station or picking the kids up at school while wearing a phony smile to cover a frightened heart.

HERE is where neighbors learned of one another’s ever more dangerous descriptions and stories that conflicted with the slogans and patriotic overtures. Never mind that the Public Information Office is organizing smiley faced family picnics while minimizing the notion that there was anything for families to fret about.

Across fences, across cocktails, in the library, at the beauty shop – you get the idea – Aviator wives hear about the deadly work SEALs are already doing. An underwater demolition specialist’s girlfriend confides in the fiancé of an electrician’s mate. One wife overhears another arguing about safety with a spouse. What to hear and say? What to hear and NOT say? If you could eavesdrop on the collective conversation, one thing seemed sure – there was something to worry about.

There was a subtle but certain acceleration in training schedules. More and more jets and props were turning in from over the surf for touch and goes at North Island. Even the amphib base was uncharacteristically conspicuous. Classes were completing ‘live’ combat drills with blank gunfire and small planes doing mock bombing runs over pre-set explosives. Previously, similar exercises had been conducted in obscure locations – but these (complete with landing craft) were held right out in the open – 200 yards south of the Hotel Del jetty. The locals and the tourists would sit on the rocks and watch the show. There was momentum toward military conflict – very gradual, very slow, very certain. It would become one of the themes for an as yet unimaginable actual war: Everybody knew – But no one said a word outside the cloister.

Still, the fretful partners of officers and sailors were in beautiful Coronado, after all. And in the daylight, both rumors and reality seemed less severe. If a wife didn’t go home to her parents, she suffered in silence and looked for friends.

In the sunshine, though, the majority shrugged.

All this talk – C’mon – It can’t happen here …