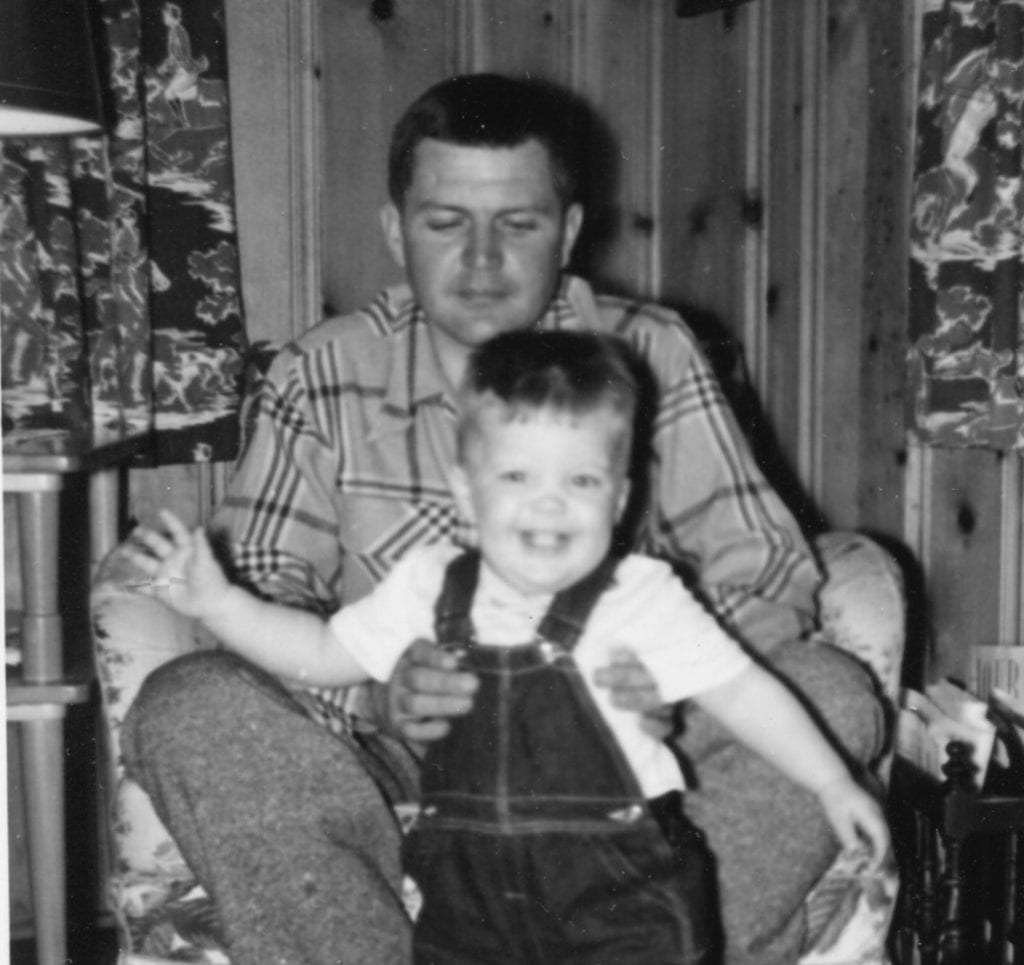

Otis Circle, Norfolk, Virginia – 1952

By Jim Stockdale Reading Time: 14 minutes

Dad always had a junk car. It was his commute to and from the carrier, the hangar, the runway, the maintenance deck – from wherever his work as a naval aviator had left him that day. Hearing his most recent clattering wreck pull in, I’d jump away from the windowsill to welcome him home with a hug hello. As early as I can remember I was always so happy to see him. He brought that wave of relaxed, unqualified acceptance that every child longs for… The easygoing reassurance in his smile as he lifted me or I ran into his arms always seemed an effortless extension of his warm heart.

From first memory, whatever the make, model, mix of rust spots, creaking hinges, missing knobs, or frayed interior – that junk car was an unspoken weekend promise of adventure. The most durable among the lot was his ’49 Plymouth Club Coupe. The subtle worn pattern faded into the cloth bench seats; softened by time and inevitable ‘slide-overs,’ yielded an almost flannel feel. I fell asleep late one night right next to Dad on that seat. He’d taken me to my first major league baseball game at Seals Stadium – and we’d waited late outside the old locker room door for Willie Mays. I would treasure his autograph through the next three moves.

In response to occasional good-natured derision about the car Dad would shrug, “Well, she’s not much to look at…” Dents and dings spotted the blue heavy hulk body – and she’d never had a wash. You could tell from the almost luminous, oily layered rainbow sheen of dust and dirt held fast by negligence. Lingering chrome trim was dulled to match. The thing was a gorgeous heap.

We had occupied a dozen different living spaces by the time I was eleven – but the old Plymouth always meant an adventure was pending. On any given weekend afternoon Dad would take me along on ‘a couple of errands’ and no matter our other assignments we would almost always wind up in a hangar ready room or at the ship or at O&R – the overhaul and repair facility where jet engines were carefully disassembled, put through proper maintenance protocols, and almost lovingly reassembled to perfection. The warehouse wooden floor was painted with a matrix of labeled squares and rectangles where parts and their accompanying screws or fasteners would, in turn, be placed upon removal – and returned in rightful, sequential pieces of the puzzle during the labyrinth of rebuilding the massive jet engine.

Test Pilot Training in Patuxent River, Maryland was a large wooden building with weather beaten exterior asbestos shingles – built on stilts at the end of the utility road. It seemed out there all alone with a backdrop of sand mounds and eelgrass across from the rest of the base – braving the wind whipping off the water.

The house we lived in was right on Chesapeake Bay and when we went swimming Dad would put me on his back and stroke out to a nearby sandbar alive with crabs and other creatures. Sometimes in the pre-dawn he would wake me and we’d walk out to the blind with our Chesapeake Bay retriever. Brownie was so strong and so happy he almost danced at the opportunity to swim out and gently tuck the ducks Dad had shot in his soft mouth – dutifully bringing them back to the shore for our walk home.

It was an idyllic setting for our young family and it seemed like upheaval when ‘the call’ came for Dad’s first squadron assignment on the west coast. He’d been testing and working on a jet that was poised to make it’s move into the rotation with the Pacific fleet. On Valentine’s Day, 1956 we boarded a prop commercial flight across the country. Stopping for gas in Dallas – we marveled at the coincidence that Dad (travelling military) was close by at Love Field prepping a dozen Chance-Vought F-8U Crusaders for their maiden flight to California. It turned out to be pretty well timed and we all arrived in Oakland on February 15th.

Wherever Dad went, I was along for the ride. Almost intuitively I knew his various workspaces required that I be polite, shake hands as prompted, and, when inadvertently provoking any hint of annoyance –curb the curiosity or questions – just watch and listen. Some of these spaces were friendlier than others for a kid. Each had its own routines, smells, and customs. For the most part west coast bases seemed friendly.

Moffett Field was relaxed and welcoming with constant coffee aroma, cigarette smoke, big comfortable Naugahyde chairs, and whiffs of hydraulic fluid and propane exhaust as planes were pushed, towed or parked in the huge space through the main door. A few plaques adorned the industrial space featuring the alternating red and white squares of the VF-211 Checkertails. A half dozen aviators were always milling around and once or twice they got it in their heads to drive out to the end of the tarmac and watch ‘touch and goes.’

Before I knew it I was climbing into a military jeep next to Dad, speeding down the endless runway. We exchanged smiles and upon arrival he picked me up and parked my butt on the hood of the jeep with the windshield at my back. “Don’t move,” was my only, firm instruction. A few minutes would pass and an F-8 would sweep in and decelerate to mimic ‘catching the wire’ in a carrier landing. Right in front of us the tires would just touch the concrete with a screech followed by fuel dumping straight into the tailpipe of the jet and BOOM! SWOOSH! –

That silver bird of prey would be going unimaginably faster and steeper by the second, climbing into the high clouds over Mountain View. The sight of the thing and the blasting sound were exhilarating for a little boy. I could hear myself yelling approval as Dad turned around to give me a wink. (Skeptics may furrow a brow – but you could actually get away with stuff like that in 1957.) After the cycle repeated six or seven times we were back in the jeep headed for the hangar and from there home – anticipating Mom’s inevitable question, “What took you so long?”

With my mouth shut I would wonder, ‘What took us so long? Are you kidding?’ How many kids have THAT kind of experience when they stop by Dad’s office on a Saturday afternoon?

A year later we lived in half a Quonset hut outside the main gate at Alameda Naval Air Station where the carriers docked. Jumping in the Plymouth we were five minutes from climbing the gangplank to the hangar deck of the USS Midway. An aircraft carrier is a living, breathing city of sailors doing their work with forklifts and hand trucks in storage facilities, stocking fuels and supplies and groceries by the ton and ‘doing maintenance’ on the huge elevators that take planes up and down from the flight deck above to the hangar decks below.

It was always busy when we would go aboard. Our routine was pretty standard –straight to the shipboard squadron ready room – and then over to OPS or Navigation or a word with the X.O., then the requisite ladders up and up onto the flight deck. I think Dad always invented some reason to go up on top. If nothing else we could just stand there together in the bright sun braced by the constant cool breeze across San Francisco Bay. The sheer enormity of the enterprise aboard ship was framed by the city across the water leading sight lines to the Golden Gate. I don’t think it was planned – but these times together helped me ‘see him’ when he was away. These were important visual markers and gave me context for his world. After all, we were very close but he was away almost as much as he was home. Nine month cruises in different squadrons and on different carriers was standard operating procedure

Dad would rub my back and tell bedtime stories about the peacefulness and tranquility of night-flying high above the clouds where he could do arabesques in the infinite air. “Getting in your flight time in” was required for aviators in any assignment – but few felt the freedom Dad described when things were that simple. It was no wonder that on the wall at home hung a framed congratulatory certificate for logging over 1000 hours of flight time in the F-8U.

With the descriptions of freedom in the air would come lessons less uplifting. He wanted me to know how fortunate we were to live in our country (and in our time) but there was never a lecture. After the first Midway cruise he touched on the fact that while ported in Hong Kong, when going ashore, he saw grown men standing at the gate ready to do any work available – any work that was needed on the base or aboard ship.

When Dad wondered about what work the men might do, an M.P. said, “Sir, they have made it clear that they will do any work needed here on base for the scraps from the aircraft carrier’s mess.” Table scraps. If you’re ever looking for a way to help a third grader understand (and remember) that the world is not fair, just before you say goodnight prayers, plant a picture of another father somewhere in the world begging for scraps so his family can eat. Exclaiming how fortunate we are as Americans doesn’t have half the staying power a simple, true description like that carries for a young boy.

(…continued)